What lies behind recent Colombia’s protests?

With Colombia still recovering from the pandemic, protests have been spreading nationwide since April 28. The trigger was the announcement of tax reform plans aiming to boost the economy. Undoubtedly, the domestic economy has seen its worst downfall during the last half-century with the gross domestic product falling by 6.8% in 2020.

In a nutshell, the tax bill was expected to drop the taxable threshold to 2.6m pesos of monthly income. Such a provision would have a profound impact on a wide range of taxpayers as well as businesses by raising the taxes payable. The accumulated economic exasperation in conjunction with the fatigue of the public liberty restrictions has led to a frustrated public that didn’t take too long to go in the streets and demonstrate. Seeing the public support plummeting towards the government, the Colombian president had no other option but to overturn his decision within four days after the announcement of the bill.

Despite the appeal of the measures, this was not enough to stop the protest, which suggests that the roots of the problem are far deeper. Prior to the pandemic, fiscal constraints and longstanding corruption are only some of the issues many Latin American countries have been experiencing. Since the virus outbreak, the regional economy received the strongest blow on a global scale, leaving room for social unrest and rising tensions.

Despite the government’s desperate efforts to suppress violent reactions with the police support, matters only worsened leading to roadblocks; deaths; clashes with the police; food and fuel shortages; and a wider public division. The following section aims to trace the reasons that led to this insurgence by checking briefly the role of violence in Colombia’s history.

The role of violence in Colombia’s history leads to the current events

Over the last century, the country witnessed countless manifestations of violence and political conflicts. In fact, Colombia’s political and social life has evolved through democratization and liberalism on one hand and the outburst of violence on the other. Corruption, state weakness, and the coexistence of paramilitary forces/guerrillas with legitimate authorities set the puzzle of Colombia’s political scene.

Based on the above, it comes as no surprise that the bipartisan system in Colombia comes hand in hand with the outbreaks of violence: two powerful parties, the Liberal Party and Conservative Party, fighting to sustain the status quo, while also resorting to violence as a force of change.

Another important attribute of Colombian society is the presence of acute disparities pushing the financially weak to extreme poverty. According to PBI Colombia, only 20% of the distributed land belongs to 99% of the population, while 80% of the land falls under the ownership of 1% of the population, which reflects the land distribution disparities in Colombia (PBI, 2018). This is a result of the accumulated failure of previous governments to carry out radical reform and modernise the archaic agrarian structures of the society.

Therefore, the current crisis did nothing more but unearth deeper wounds of the Colombian society – poverty, regional disparities in health capacity and funding, untreated violence; as well as open the debate for some urgent measures such as the introduction of a universal basic income.

One might advocate that protests consist of a peaceful way to express the public discontent over the current economic and social crisis. This is true for Colombia’s case as well. However, events took shortly the wrong turn, with civilians losing their lives amid clashes between police and armed groups. Such hostilities have already provoked the UN condemnation for police abuses, human rights violations and deaths of civilians that were peacefully protesting against the government tax reforms.

It is apparent that the country is at war. A call for radical changes and new leadership is deemed necessary to avoid further political ramifications. To better understand better Duque’s share of responsibility in the unravelling of the current events, the next section aims to uncover the president’s profile.

Examining Duque’s profile

Since Duque’s succession to power in August 2018, the president has suffered low rates of approval. His party, Centro Democratico, comes from the conservative right. Despite the odds, Duque managed to stay in power and re-invent himself during the pandemic by reaching a 53% of approval rate in May 2020. How did he succeed in this?

First of all, he moved his government to the centre in the absence of other political competitors. Avoiding past mistakes was a smart move for Duque that widened his public support and refrained his party from the polarization of the left or right.

Second, his quick response to the mitigation of the virus has worked in his favour. By centralizing the public order decisions and decreeing a national lockdown, his technocratic skillset has helped the country to stay united. Among his main achievements: the re-alignment of the public resources and the regional coordination of the health sector.

Third, the introduction of unconditional cash transfers was one of the most important socioeconomic measures deployed by the government to tackle the high poverty and unemployment rate. To achieve this, the national general budget was used as a source to fund the state emergency. By issuing government bonds and loans, however, national debt skyrocketed – leading to the largest public debt in Colombia’s history.

As time passed by, public support shifted negatively towards the government. A tired nation from the strict lockdown started to question Duque’s tactics. The use of the constitutional provision of “economic, social, and ecological emergency” – that allowed the president to take quick decisions while bypassing regional and departmental levels authorities – was the epicentre of criticism from his political opponents. (Acosta et al, 2021).

Another important point the government received criticism in the pre-COVID period was: one, the failure to honour the 2016 deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC); two, the inability to introduce radical reforms that would resolve the existing disparities. These two reasons triggered the 2019 protests, which gained such momentum, that violence reached its peak – the largest the country has seen in many years. What made things worse was the government’s inability to protect its people from the rising violence – topped by the killing of indigenous people, while trying to protect their territory from the rebel group FARC.

The final stroke that brought protests back in April was Duque’s decision to reopen the discussion for the 2019 tax reforms. According to the government’s rationale, these reforms were the only resort to cover the budget hole. Nonetheless, the rise of public disapproval led to the appeal of the bill shortly after its announcement, which does not explain why the protests did not stop; the main objective was achieved. The next section aims to analyse the new claims that have arisen from this upheaval.

What the protesters demand

To answer why Colombians continue protesting, it is essential to see the bigger picture. The real causes are deeply rooted in Colombian society and stem from the existing disparities. This is why protesters now call for further social, political, and economic reforms.

In terms of battling inequality, some voices request reforms to guarantee equal opportunities to employment and education. Also, the introduction of a universal basic income is another topic widely discussed. To this day, almost 40% of the country’s income is earned by 10% of the population (Colombia Reports, 2021). For this reason, members of the parliament have also proposed a five-month emergency basic income to be granted to vulnerable families.

Second, the suspension of police enforcement attacks against the public and the adjudication of committed crimes by the police is an absolute condition for the termination of the protests. Claims that corruption has eroded police forces justify the scepticism towards the riot police. Amid fears of paramilitaries and guerrillas infiltrating the grievances, Duque’s administration decided to intensify the police presence and take radical measures to suppress them via the use of tear gas and in some cases ammunition. Despite protesters’ demands, Duque refuses to concede and insists to proceed with police reforms. The recent deployment of 7000 troops is expected to clear the main highways from roadblocks that hinder the transportation of goods and cause further food shortages.

A question that arises here is to what extent such measures really protect the vulnerable from paramilitary forces, which have under their control certain territorial areas in Colombia. Testimonies indicate that the local population often becomes a recipient of hostilities directed by armed groups as retaliatory behaviour towards the state. The unfulfilled peace agreement of 2016 is likely to cause further disputes. It is no coincidence that those deeply affected by the clashes live in rural areas, where extreme poverty has increased in cities like Quibdo by 30% with figures amounting to 9% (BBC, 2021b).

With all the above in mind, the next section discusses how things might unfold in Colombia over the coming months.

What the future holds for Colombia

Estimates show that the polarization of the Colombian people will continue until the next elections in May 2022. It’s only left to be seen whether the governing party Centro Democratico will manage to achieve what the previous governments have failed: to bring stability and security in a nation deeply hidden by the pandemic – not only financially but also socially.

First of all, any fiscal initiatives should alleviate and not deepen poverty. Indeed, tough decisions might be inevitable for the rationalisation of the Colombian economy from the current crisis. However, the government will need to communicate such reforms in a clear way to the public and promote competitiveness that will encourage foreign investment in the long term; uniting the public rather than resorting to police enforcement is more likely to restore peace and attract foreign investors.

In the social context, the need for reforms will play also a central role in the restoration of the government’s credibility. Socio-political reforms need to be horizontal and vertical, allowing the state to maintain its basic monopolies in its whole and not partial territory. Although the country has been urbanised, its rural inequalities have not been resolved, while its agro-exporting model remains in place. Awarding incentives to switch over to other crops than coca could help the country to maintain control over the most critical parts of the economy as well as minimize the interference of non-state actors in the domestic market.

Finally, strengthening the police presence and militarising regions infiltrated by violent forces can only be an effective measure in the short term. In the long term, however, building a better level of trust and empathy with the public will help the government to restore order internally.

So much is owed to a nation that despite its long history of enduring violence, has developed “a bona fide republican experience in many fundamental senses” (Sanín et al, 2006). Certainly, such an attempt will not be an easy task and will unleash the reaction of many free riders that govern in parallel with the official authorities. However, maintaining clear communication channels and negotiating with the lobbyists can be powerful tools in the hands of that government that will decide to turn over a new leaf to Colombia’s history and end violence by simply not resorting to violence to treat violence.

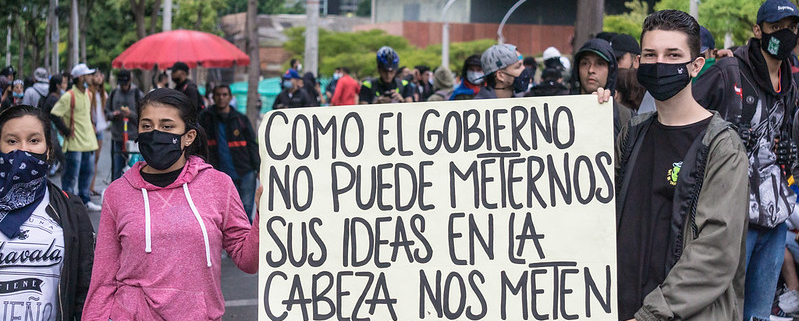

Photo: Oxi.Ap. Paro Nacional Colombia (2021). Source: (flickr.com) | (CC BY 2.0)

Bibliography

ACLED (2020) Disorder in Latin America: 10 Crises in 2019, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24685 [Accessed 28 July 2021]

Acosta, C., Uribe-Gómez, M. and Velandia-Naranjo D. (2021) Colombia’s response to Covid 19: Pragmatic Command, Social Contention, and Political Challenges, Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19 (pp. 511-521), ANN ARBOR: University of Michigan Press, Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.11927713.30 [Accessed 29/07/2021]

BBC (2019a) Colombia protests: Three dead as more than 200,000 demonstrate, BBC News, 22nd of November, Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-50515216 [Accessed 27/07/2021]

BBC (2019b) Colombia violence: Dissident rebels kill indigenous leader, BBC News, Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-50233674 [Accessed 01/08/2021]

BBC (2021a) Colombia withdraws controversial tax reform bill after mass protests, BBC News, 2nd of May, Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-56967209 [Accessed 27/07/2021]

BBC (2021b) Why Colombia’s protests are unlikely to fizzle out, BBC News, 31st of May, Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-56986821 [Accessed 27/07/2021]

Colombia Reports (2021) Poverty and inequality, 6th of March, Available at: https://colombiareports.com/colombia-poverty-inequality-statistics/ [Accessed 01/08/2021]

Daniels P. J. (2021) Further unrest in Colombia as talks stall between government and protesters, The Guardian, 29th of May, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/29/further-unrest-in-colombia-as-talks-stall-between-government-and-protesters [Accessed 27/07/2021]

Flannery P. N. (2021) Political Risk Analysis: What Do Investors Need to Know About Colombia’s 2022 Election? Forbes, 12th of July, Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/nathanielparishflannery/2021/07/12/political-risk-analysis-what-do-investors-need-to-know-about-colombias-2022-election/?sh=19e72d8cf0f9 [Accessed 28/07/2021]

International Crisis Group (2020) Leaders under Fire: Defending Colombia’s Front Line of Peace, International Crisis Group, 82: 21-25, Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep31392.7 [Accessed 28/07/2021]

PBI Colombia (2018) So much land in the hands of so few, Land: Culture and Conflict, 2nd of January, Available at: https://pbicolombia.org/2018/01/02/so-much-land-in-the-hands-of-so-few/ [Accessed 01/08/2021]

Rodriguez M. S. (2021) More Than a Battle for the Walls: Social Unrest and Duque’s Repression in Colombia, Australian Institute of International Affairs, 25th of July, Available at: https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/more-than-a-battle-for-the-walls-social-unrest-and-duques-repression-in-colombia/ [Accessed 27/07/2021]

Sanín Guitiérrez F., Acevedo T and Viatela M. J. (2007) Violent Liberalism? State, Conflict and Political Regime in Colombia, 1930-2006, An Analytical Narrative on State-Making, Working Papers Series No.2, Crisis States Research Centre (DESTIN) LSE, London, Available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/international-development/Assets/Documents/PDFs/csrc-working-papers-phase-two/WP19.2-state-conflict-and-political-regime-in-colombia.pdf [Accessed 28/07/2021]

Stott M. (2021) Colombia’s social unrest could spread across Latin America, The Financial Times, 17th of May, Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/998a4ba0-dc7b-4cac-b831-50f64ca58bbf [Accessed 27/07/2021]

The Economist (2021) Colombia, Intelligence Unit, Available at: http://country.eiu.com/colombia [Accessed 28/07/2021]

Third Way (2020) World Leaders: A Pronunciation Guide, Third Way, Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26170 [Accessed 28 July 2021]

Turkewitz J. (2021) Why are Colombians Protesting? The New York Times, 18th of May, Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/18/world/americas/colombia-protests-what-to-know.html [Accessed 27/07/2021]

United Nations (2021) Colombia: UN and OAS experts condemn crackdown on peaceful protests, urge a thorough and impartial investigation, United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=27093&LangID=E [Accessed 01/08/2021]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!